During the late ’70s, James Reese noticed a striking correlation between young defendants’ inability to read and having a criminal record.

As a Los Angeles Municipal Court judge in Compton, Reese had sentenced scores of juveniles convicted of misdemeanor offenses to perform community service in lieu of doing jail time. One day, he received a call from a woman in charge of the community-service program. “She told me that of the 80 or 90 boys I sent to her, she could only place about 20 in projects because they were basically illiterate,” said Reese, who is now retired from the Los Angeles County Superior Court bench. “They couldn’t fill out the application form. Some couldn’t even sign their names.”

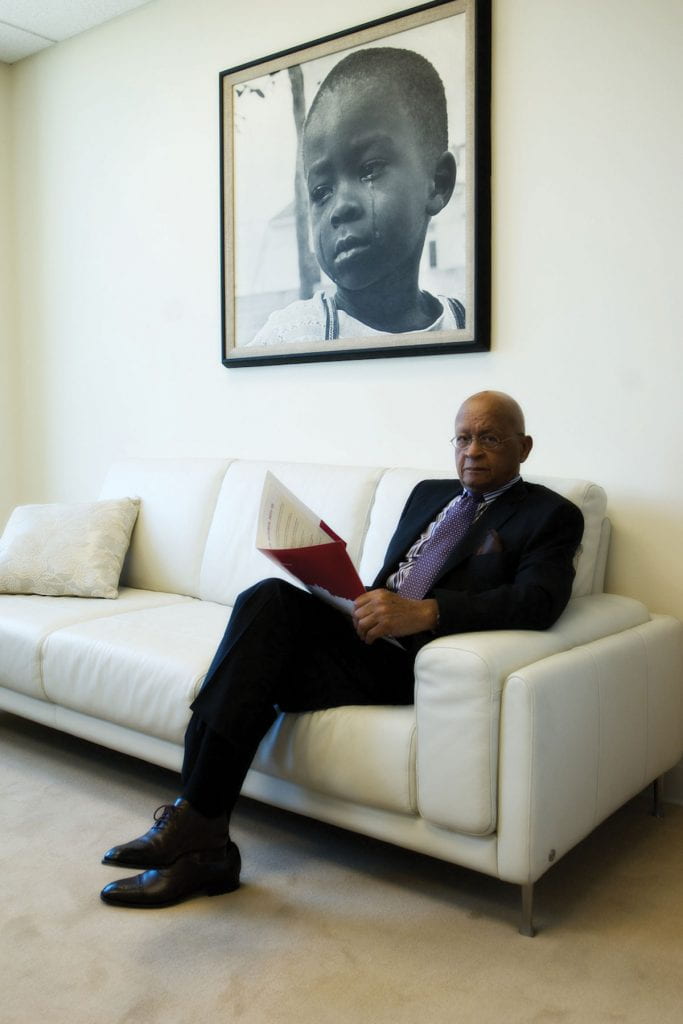

That eye-opener—combined with his earlier observations of client illiteracy when he was a defense attorney and a legal-aid program organizer—led Reese to fund “Kinder 2 College.”

A USC pilot project, the initiative will pair 100 boys in first through third grade with mentors who devote four or five hours a week to developing their reading skills. Local principals and teachers select the boys based on socio-economic factors such as an absent father, a family member on drugs, living in poverty, and other criteria.

In addition to his legal-system experiences with illiteracy, Reese, who has lived in the Lafayette Square area of mid-town Los Angeles since 1956, unearthed sometimes surprising results when he conducted informal research on education and incarceration.

For example, there is a glaring difference between the cost of educating a teenager who has entered the juvenile justice system and the cost of remedial training in grades one to three. “In the early years, it’s about $1,700. Once he’s in the juvenile justice system, it’s more than $10,000,” Reese said.

There was also the shocking discovery of how some states plan their prisons. “I found that the State of California and eight or nine other states were studying the reading scores of fourth-grade males to determine how many prison cells to build eight years out,” he said. “That means we’re warehousing these boys.”

Conversely, said Reese, “I know what can happen to boys if they’re given the right encouragement. It’s not just about giving them the technical assistance of tutoring. It’s about instilling self-confidence.”

Reese firmly believes “Not everyone can go to college, but they should all learn to read so that they can vote, can read a newspaper. If you can’t pass a fourth-grade reading test, how can you know what’s going on? It’s so basic. It’s being prepared to be a participating citizen.”

His own early preparation began in New Orleans. There, despite being in a segregated school system and having an alcoholic father who made family life difficult, he benefited from “the dedication, reinforcement, and support that teachers gave students, and I was a recipient of that throughout my education.” Reese later taught elementary school in that city before he entered the Army during World War II, and then moved to Los Angeles.

In 1946, on the GI bill, he received his juris doctorate degree from the USC Gould School of Law. Even though he was the only African American student in the school at the time, he felt at home.

That positive experience was a strong reason he established “Kinder 2 College” at USC. “I’m getting all the support an institution can give me to put this project into effect,” Reese said. “I envision that USC, with all of its contacts, reputation, and resources will be able to take this project and create a solution that will get national attention. If any institution can do it, it’s USC.”