It’s a Thursday afternoon and Sina Kiamehr, over 6 feet tall and clad in a white lab coat, goes up to the fourth floor of the pharmaceutical sciences building. He walks into a lab, checking in at the whiteboard to see what he’ll be working on that day.

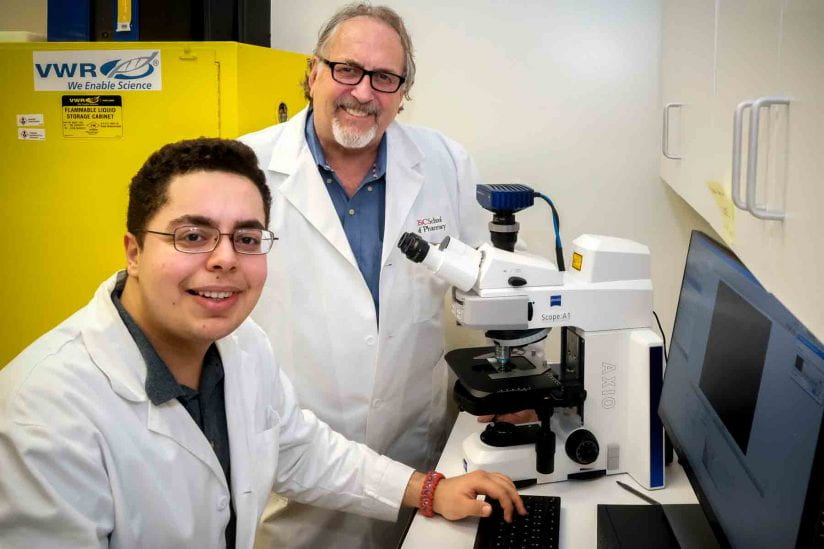

Kiamehr is a 17-year-old high school senior, but it would be easy to mistake him for a graduate student: He’s in the pharmaceutical lab of Professor Daryl Davies at the USC Health Sciences Campus nearly every day.

He’s one of the leads on a research project looking at how the microbiome — as in gut bacteria — might be different in alcoholics. The team is looking at whether certain bacteria can foster alcoholism and if alcoholics could more easily achieve sobriety if they received a transplant of healthy bacteria. Kiamehr, 17, works in a lab that studies the role of the microbiome in alcoholism.

“Sina is actually directing some of my undergraduates,” said Davies, a USC pharmacologist. “They don’t put nearly as many hours as he does into the project.”

Kiamehr is in USC’s STAR Program, which stands for Science, Technology and Research, and teams up high school students with researchers from the Keck School of Medicine of USC and the USC School of Pharmacy. STAR students come from underrepresented groups: 92 percent are people of color and 55 percent are female.

The program is a partnership with Francisco Bravo Medical Magnet High School and supported by a USC Good Neighbors grant.

Off to college

Kiamehr is one of roughly 50 students currently in the program, according to Davies, who is also the program director. More than 600 students have gone through STAR and all have gone to college, 98 percent of them to top-tier universities such as Columbia, Princeton and Stanford.

Kiamehr has his own success story: He received early acceptance to Harvard University.

“I always aimed for it,” Kiamehr said, a senior at Bravo. “I always dreamed of it.”

Since he was little, his parents talked about the importance of education. Growing up in Iran, he heard them talk about a U.S. school called Harvard, but it didn’t hit home until he moved here four years ago.

At the time, he only spoke Farsi. “The language barrier was the biggest challenge,” he said.

Kiamehr is the son of a pharmacist and school psychologist, and medicine is a part of his family’s DNA. But if he had to pinpoint when he decided to pursue it as a career, he thinks of his cousin.

Only a year older than her, he remembers going with her to the hospital when she was 6 and 9 years old. She was born with heart defects and had to receive open-heart surgery, he said.

“I appreciated how people were working hard to help her,” he said. “I overheard from family members that she might not survive. She did and it was because of the surgery.”

His goal is to become a cardiovascular surgeon, just like the people who saved her.

And even though medical school is still a ways off, Kiamehr is getting hands-on training with USC School of Pharmacy faculty and students.

Daily research

Monday through Friday, for a few hours every day, Kiamehr is there working on research. He spends two to four hours a day on public transit, waking up at 5:30 a.m. in Sherman Oaks to catch the bus to his school in Boyle Heights, then sometimes stays at the lab until 5 or 6 p.m. before jumping on the bus again.

Every day is different. Sometimes he’s collecting data, pipetting or examining DNA. Other days he might be weighing or collecting fecal samples.

It’s a really cool thing to be a co-author on an actual scientific publication.

Sina Kiamehr

The team recently gathered enough data to publish findings. “I just think it’s a really cool thing to be a co-author on an actual scientific publication,” Kiamehr said.

The students in the STAR program often get to present their research at science fairs and competitions. Recently, they went alongside graduate students to present their research at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center.

Davies believes working as a junior scientist in high school is a good preparation for life. The students learn to think critically and communicate their questions. They also learn that there can be a lot of failures before there are successes, he said. That’s part of the life of a scientist.

“In my mind, a lot of these students will advance and take this maturity to everything in their lives,” Davies said.

More stories about: Community Outreach, Pharmacy