“Come read with me.”

Those can be some of the most powerful words in the development of any child’s ability to read and write. For children who are deaf or hard-of-hearing and living in bilingual homes, the “come read with me” invitation becomes even more crucial to literacy development.

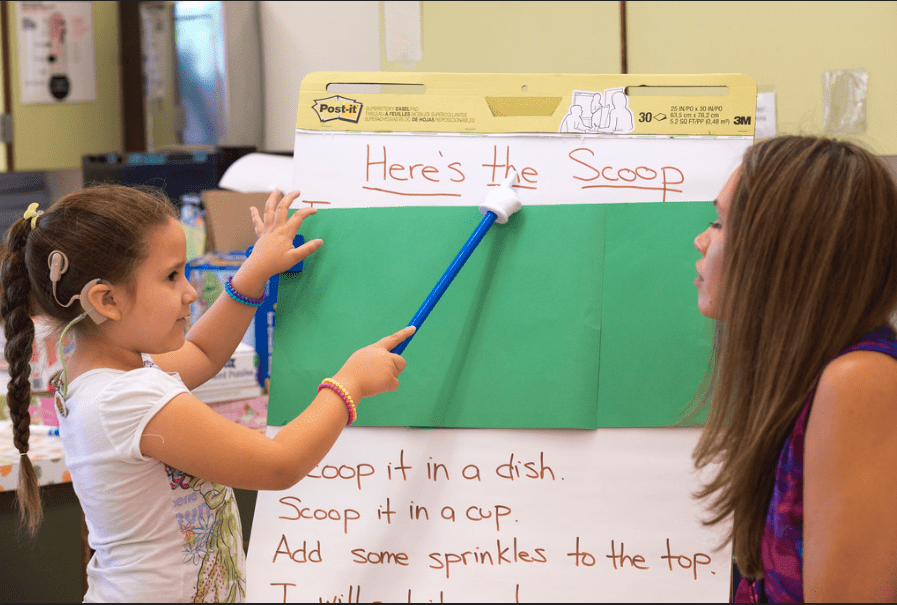

That’s why the USC Caruso Family Center for Childhood Communication is getting creative in tackling challenges that children with hearing loss face in learning to listen, talk, read and write. Its innovative program — called “Come Read With Me” — is a three-week summer intervention and grant-funded research project designed to help develop early literacy skills in oral deaf and hard-of-hearing children from bilingual (Spanish-English) homes.

Through the program, USC seeks to support everyone involved in a child’s education — the children, their parents and teachers of the deaf and hard-of-hearing in the greater Los Angeles area.

The program is the creation of an interdisciplinary team of experts: educational specialist Debra K. Schrader, audiologist Karen C. Johnson, speech language pathologist Dianne Hammes Ganguly and biostatistician Laurel M. Fisher. From 2013 to present, Come Read With Me has more than 50 children from ages 4.5 to 8 years, 41 parents and caregivers from homes in which Spanish is spoken by at least one parent, and 16 full-time teachers and language specialists in special education programs and private practice. The program primarily serves families and educators in Los Angeles and the surrounding area.

The results are promising.

Children become active readers and writers

During the summer session, children receive daily lessons in shared reading, dialogic reading, writing and awareness of the sounds of speech. They learn concepts of print and word knowledge developed through interactions with peers, parents and teachers.

Parents say their children are more engaged in both reading and writing at home. After a three-week session, youngsters demonstrate increased conversational turn-taking during reading activities and more purposeful interaction during writing activities.

Parents become change agents

Parents receive 12 hours of group instruction on how to develop their children’s reading and writing at home. With this knowledge, they start viewing themselves as change agents who can actively help their children gain literacy skills. They share their new strategies with other parents, and many families have returned for another summer in the program.

“Parents are hungry for information and knowledge,” said Johnson, who is principal investigator of the research project and an associate professor of clinical otolaryngology at the Keck School of Medicine of USC. “Their enthusiasm is inspiring. As one mother told us: ‘I think I get it — books are where my daughter will gain her wisdom.’ ”

John Niparko, the late chair of the USC Caruso Department of Otolaryngology-Head & Neck Surgery who championed this program from the start, had noted instances of deaf children using their new literacy skills to teach others in their family to read.

Teachers feel more prepared

Teachers report feeling more equipped to help deaf and hard-of-hearing students in the classroom. They receive five days of professional development designed to give them new strategies in teaching phonological awareness, shared reading and writing. They also benefit from daily coaching and mentoring during the summer program.

“Teachers are taking this to the classroom and to their peers,” Schrader said. “Participants have started sharing their new knowledge with other teachers through professional development at their schools. This is such an effective way to support greater language and literacy acquisition.”

“Come Read With Me is having a ripple effect,” Hammes Gangly said. “Children are more engaged in reading and writing activities. Parents are learning new ways to help their children become better readers and writers. And teachers are gaining additional skills in helping parents and children during this learning process. Supporting all three groups is critical to child success.”

The 2016 summer session concluded at the end of July.

By Meg Aldrich