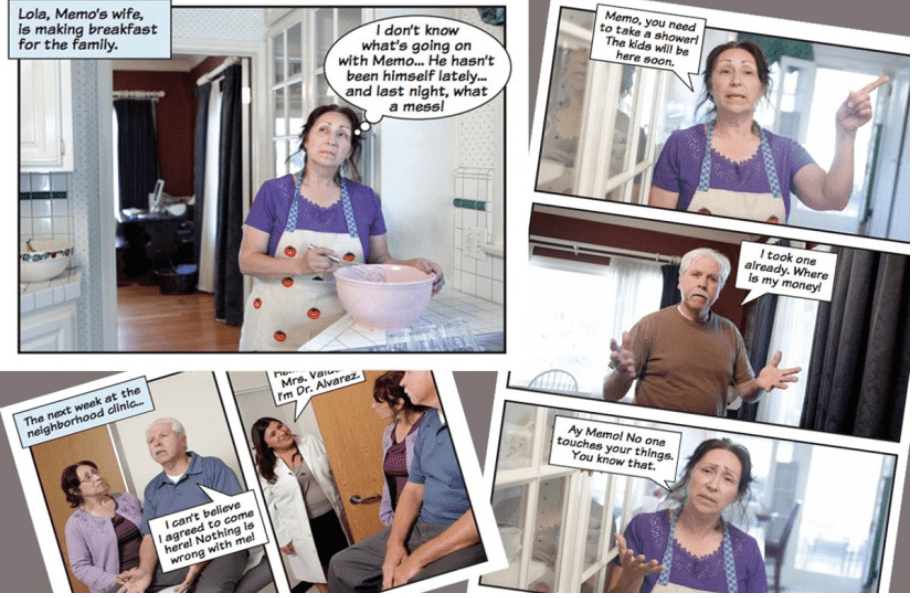

When aging grandfather and Mariachi musician Don Memo Valdez becomes increasingly forgetful and irritable, his family starts to worry. Don Memo’s wife expresses dismay at her husband’s memory lapses while his daughter-in-law, a nurse, suggests he should see a doctor. However, his son Guillermo dismisses the changes in his father’s behavior as simply a natural part of the aging process.

The fictional Valdez family appears in Forgotten Memories, a new audiovisual novella developed from a fotonovela — a small pamphlet akin to a comic-book, with photographs instead of illustrations, combined with dialogue bubbles. Targeted at the Latino community, it was co-developed by Margaret Gatz, professor of psychology at the USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences and Mel Baron, associate professor of clinical pharmacy at the USC School of Pharmacy. Forgotten Memories aims to inform its audience about the early signs of Alzheimer’s disease and dementia and encourage them to take action.

“Too often, forgetfulness and other signs of dementia are still being dismissed — even in the medical community — as, ‘It’s just old age and nothing can be done about it,’” said Gatz, who also holds joint appointments in gerontology from the USC Davis School of Gerontology and in preventive medicine from the Keck School of Medicine of USC.

Aiming to make brighter endings more common

After struggling to come to terms with Don Memo’s symptoms, his family consults a physician who diagnoses his dementia. With his family’s newfound understanding and acceptance of his condition, the story ends on an upbeat note as Don Memo connects with his granddaughter over music.

However, Don Memo is one of the lucky ones. Studies show that low diagnosis is particularly acute among Latinos, where lack of physician awareness and cultural sensibilities may cause families to delay consulting a physician about an older relative who is showing signs of dementia for months — or even years.

Gatz, whose research focuses on the mental health of older adults, is determined to change that. Along with colleagues Baron, Greg Molina and Brad Williams of the USC School of Pharmacy, Gatz developed the fotonovela while she was serving as director of the education core for the USC Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center.

“Forgotten Memories grew from Baron’s experience with using the fotonovela format to inform the Latino community about other diseases and our knowledge at the Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center about dementia,” Gatz said. “We focused on one particular message: People need to recognize the early signs of dementia and get the affected person to a physician as soon as possible.”

Gatz, Baron, Molina and Williams decided to adopt the fotonovela format because they believed it would get this message across to their target audience in a way that was accessible, familiar and fun.

“The fotonovela is a traditionally Latino format — it’s the kind of popular magazine that reads a bit like a soap opera and you find at the grocery store,” Gatz said. “We figured people might grab it and actually read it before they would pick up something that looks like a boring pamphlet.”

A valuable tool made widely accessible

After Baron began adapting fotonovelas to an audiovisual format, it was a logical next step to make Forgotten Memories into an audiovisual novella. On May 31, after Molina reached out to publicize Forgotten Memories, Los Angeles PBS station KLCS aired the audiovisual novella that was developed from the original fotonovela using the voices of the actors who are pictured in the print version. It aired again on June 7.

“People watch television,” Gatz said. “It’s a very effective way to distribute a message and reach people who might say, ‘Oh my, I think this applies to someone in my family.’ ”

But even when family members do bring an elderly relative to see a doctor, the disease still often goes undiagnosed, Gatz said. “Dementia is often under-recognized, even by physicians. For this reason, we distributed the fotonovela to doctors’ offices and the Latino Diabetes Association to educate professionals who are in a position to refer people for more expert assessment.”

Thousands of copies of Forgotten Memories have been distributed at health fairs and talks, and it is listed on national information websites about dementia, including the Alzheimer’s Association’s site and the National Institutes of Health information website about Alzheimer’s disease.

Early assessment is key

Carlos Rodriguez, a Provost Fellow and Ph.D. candidate in clinical psychology at USC Dornsife, has chosen to write his doctoral thesis on research he has conducted to evaluate the efficacy of the fotonovela in educating its target audience about dementia and influencing their behavior.

“We are pitting Forgotten Memories against a standard informational brochure on dementia,” Gatz said. “People took a pretest, read the fotonovela or the standard brochure, took a post-test and some weeks later took the test again. What we’ll be able to compare is how much people learned from the educational outreach, whether the fotonovela format led them to learn more, or not, and also how it affected their behavioral intentions.”

Gatz and Rodriguez stressed the importance of getting an early assessment when symptoms of dementia begin.

“It’s a lot easier to find out early on what kind of etiology is the driver for dementia,” Rodriguez said. “Once significant impairment has set in, it becomes more difficult to differentiate what kind of dementia is present.”

A diagnosis helps families access resources and information on how to care for their relative. An early diagnosis can mean patients may still be able to formulate a plan for their life and future care.

Early diagnosis might also avoid missteps. “There might also be cognitive alterations present that are potentially reversible if they turn out not to be dementia,” Rodriguez said.

A message that translates

“I really liked the fact that the fotonovela focuses on a Latino family here in LA,” Rodriguez said. “It’s a tight-knit family so they become aware of changes in grandpa’s behavior fairly quickly. However, they don’t know what to do about them or even whether they should be talked about. The fact that Latinos have a lot of respect for their elders may contribute in some cases to their delay in seeking health care.

“By having these dilemmas modeled by a Latino family who go through figuring out what these symptoms mean and struggle with what can be done about them, we hope to help other families recognize dementia symptoms and seek medical advice more quickly.”

By Susan Bell